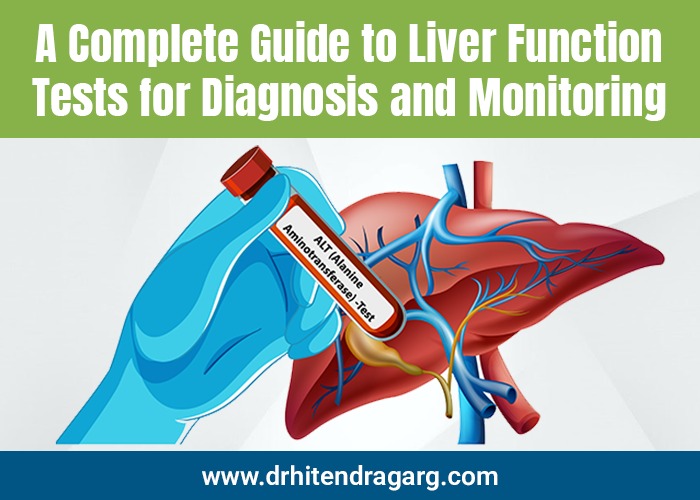

Liver function tests (LFTs)—often called liver blood tests—are a group of blood markers that help doctors detect liver injury, assess how well the liver is working, and monitor recovery or progression over time. Used correctly, LFTs can flag silent problems early and guide next steps such as imaging, viral hepatitis testing, or fibrosis assessment.

What’s included in “LFTs”?

Most panels report some or all of the following:

- Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) – enzymes released when liver cells are injured. Marked ALT/AST elevation usually indicates hepatocellular injury.

- Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and Gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) – rise with problems in bile formation or flow (cholestasis) and can also increase in certain bone disorders (ALP).

- Total and direct (conjugated) bilirubin – elevated when the liver can’t process or excrete bile properly, or when there is excess red cell breakdown.

- Albumin – a protein made by the liver; low levels suggest reduced synthetic function or chronic disease.

- Prothrombin time / INR – reflects the liver’s ability to make clotting factors; prolonged INR signals impaired synthetic capacity and can be urgent.

When are LFTs recommended?

Doctors order LFTs when you:

- Have symptoms (jaundice, dark urine, pale stools, itching, fatigue, right-upper-quadrant pain)

- Have risk factors (alcohol use disorder, viral hepatitis exposure, obesity/metabolic syndrome, certain medications or supplements)

- Need monitoring for a known liver disease or a potentially liver-toxic medication

- As part of a routine panel, where an unexpected abnormality may appear

Guidelines emphasize interpreting any abnormal result in a clinical context and confirming with repeat testing or additional work-up rather than ignoring “mild” abnormalities.

How to prepare for an LFT

A colonoscopy is done to find and prevent serious stomach and intestinal issues. Doctors recommend it forUsually, no special preparation is required. Your clinician may ask about recent alcohol intake, strenuous exercise, medicines/supplements, and fasting status because these can subtly influence results; patient-facing instructions are summarized by MedlinePlus

Understanding LFT patterns

Doctors first look at the pattern of abnormalities:

- Hepatocellular pattern – ALT/AST disproportionately high compared with ALP (think viral hepatitis, ischemia, toxins, autoimmune hepatitis, fatty liver flares).

- Cholestatic pattern – ALP and GGT predominate (think gallstones, biliary obstruction, primary biliary cholangitis or sclerosing cholangitis, drug-induced cholestasis).

- Mixed pattern – both sets elevated.

- Impaired synthetic function – low albumin and/or prolonged INR (seen in advanced or acute severe liver disease).

The magnitude of the enzyme rise helps triage urgency. AASLD suggests an initial work-up with CBC, ALT/AST, ALP, bilirubin, PT/INR, viral hepatitis panel, iron studies, and abdominal ultrasound—escalating to autoimmune and other testing if elevations are persistent or significant.

Common causes of abnormal LFTs

- Metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD/NAFLD) – linked to obesity, diabetes, dyslipidemia; typically mild ALT>AST elevations.

- Alcohol-related liver disease – AST often > ALT (classically ~2:1).

- Viral hepatitis (A, B, C, E) – may cause marked hepatocellular elevations.

- Drug- or supplement-induced liver injury (DILI) – patterns vary; careful medication/supplement history is key. FDA guidance underscores frequent early monitoring when starting drugs with potential hepatotoxicity.

- Biliary tract disease (stones, strictures, tumors) – cholestatic pattern with raised ALP/GGT and bilirubin.

- Autoimmune liver diseases (AIH, PBC, PSC) – may present with any pattern; require specific serologies and sometimes biopsy.

- Ischemic or congestive hepatopathy, muscle disorders (can spuriously raise AST/ALT), celiac disease, and thyroid disorders are less common but important.

Monitoring: what changes over time?

- ALT/AST generally fall as hepatocellular injury resolves.

- ALP falls slowly (half-life ≈ 7 days), so it can stay elevated for weeks after obstruction or cholestatic injury improves—useful when counseling patients on recovery timelines.

- Bilirubin may lag behind transaminases in cholestasis; INR and albumin track liver synthetic function and prognosis.

How often to repeat? It depends on the diagnosis and treatment. In potential DILI, regulators advise checking enzymes and bilirubin every 2–4 weeks early after starting a suspect drug. In chronic diseases, the cadence is tailored to risk and therapy.

What happens after an abnormal result?

Evidence-based algorithms (BSG, AASLD, ACG) recommend:

- Confirm and characterize: repeat LFTs (unless severely abnormal), review medications/alcohol, screen for viral hepatitis, check metabolic risks, and perform an ultrasound if cholestasis or persistent abnormalities.

- Stratify fibrosis risk: in at-risk patients (e.g., MASLD, alcohol-related disease), use non-invasive fibrosis scores such as FIB-4 as a first step to rule out advanced fibrosis; if elevated, follow with elastography (FibroScan/VCTE) or second-tier tests per EASL’s 2021 algorithm.

- Targeted testing: autoimmune markers (ANA, ASMA, AMA), iron studies, ceruloplasmin (young patients), alpha-1 antitrypsin, celiac serologies—guided by age, pattern, and clinical clues.

- Refer when needed: urgent referral for jaundice with high INR, suspected acute liver failure, or evidence of advanced chronic disease.

Special situations

- Pregnancy: ALP can be physiologically higher (placental source). Persistently abnormal bile acids or LFTs warrant evaluation for intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy.

- Children: age-specific ranges and pediatric causes differ; follow pediatric-specific guidance.

- Athletes / intense exercise: can transiently raise AST/ALT; interpreting alongside CK and history helps differentiate muscle vs liver origin.

- Bone disease: isolated ALP elevation with normal GGT suggests a bone source rather than liver.

Limitations of LFTs

- “Normal LFTs” ≠ “normal liver”. Fibrosis can be present with normal enzymes. That’s why risk-based fibrosis assessment (FIB-4 → elastography) is recommended in primary care for at-risk groups.

- Not specific to a single diagnosis. The pattern + history + imaging/serology is what makes the picture clear.

- Reference ranges vary by lab and population; always interpret against your lab’s cut-offs.